Crowdsource Research Appeal: Dom Gregory de Wit OSB

Dom Gregory de Wit, a Benedictine artist, left a profound yet often overlooked legacy through his monumental murals and religious artworks across Europe and the U.S. A 2025 retrospective in Germany aims to document his contributions, with organizers seeking additional information on his lesser-known works.

24 March 2025

by Edward Begnaud

gregorydewit.info@gmail.com

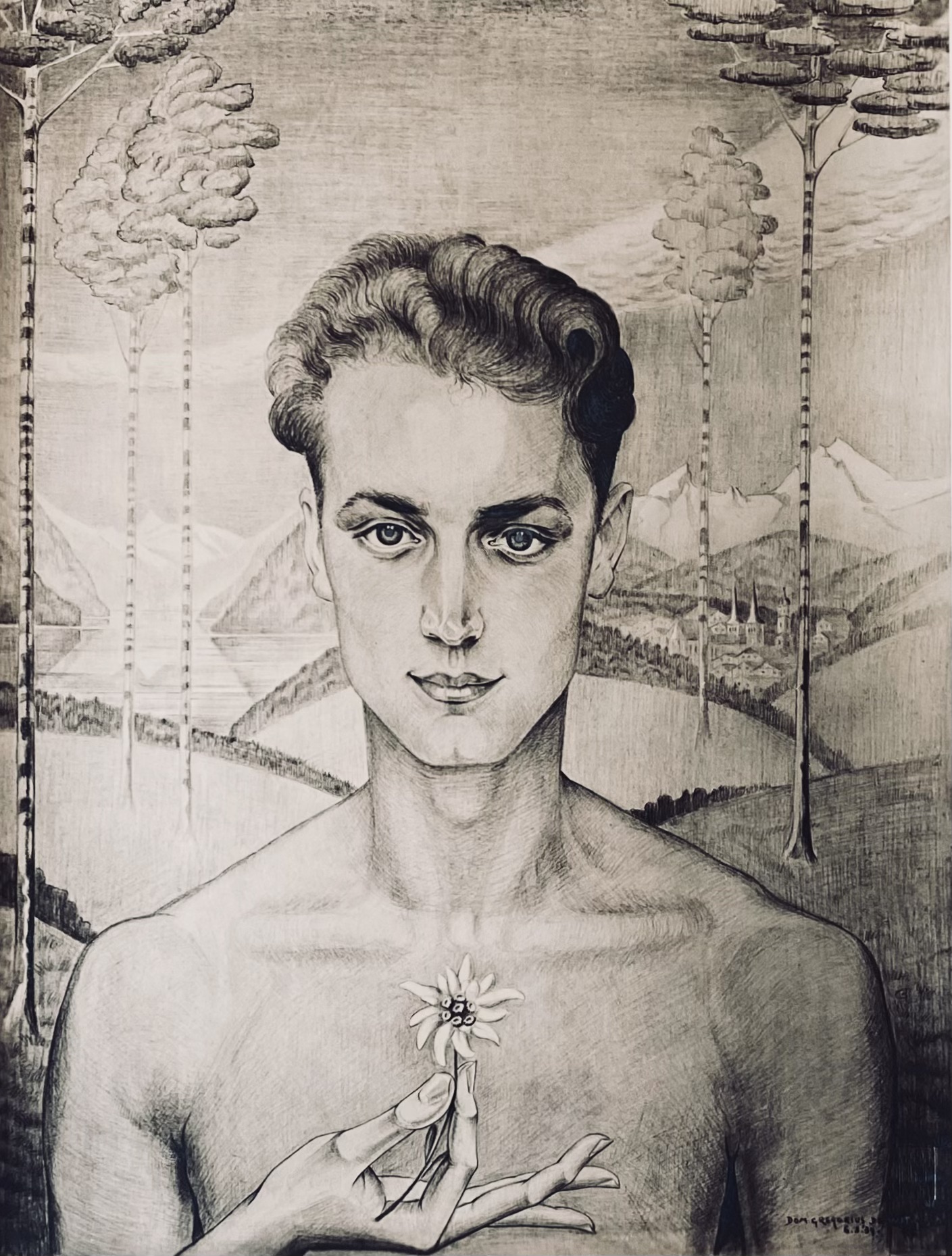

The influential role that Benedictines have played in all aspects of Church life is unquestionable. In the long list of significant figures leading the way, many others of “good zeal” (RB 72:1) are passed over. If the silent walls of the cloister could only speak, much would be learned from the descendants of Benedict that never became famous. One such monk, who in fact titled his memoirs, “I’ll Never Be Famous,” was the artist Dom Gregory de Wit (Hilversum, Netherlands 1892 — Oberems, Switzerland 1979; professed, Mont César (Keizersberg) Abbey, Louvain, Belgium, 1915). Through his hands, walls not only learned to speak but were animated to proclaim the Gospel from generation to generation.

People in the United States who have come to know the work of de Wit more than likely first encountered his monumental murals at one of a short list of places: Saint Meinrad Archabbey, Saint Meinrad, Indiana; Sacred Heart Catholic Church, Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Saint Joseph Abbey, Saint Benedict, Louisiana; or, Saint Brigid Catholic Church, San Diego, California. Those in Europe have a considerably shorter list from which to draw. Since the conversion of Saint Joseph Church in Hilversum, Netherlands, to apartments, the most significant locations with art in situ are: the monastic refectory at Saint Michael, Metten, Germany; Notre Dame de Bon Secours, Pontisse, Belgium and; the rare mosaics at Saint Lawrence, Antwerp, Belgium.

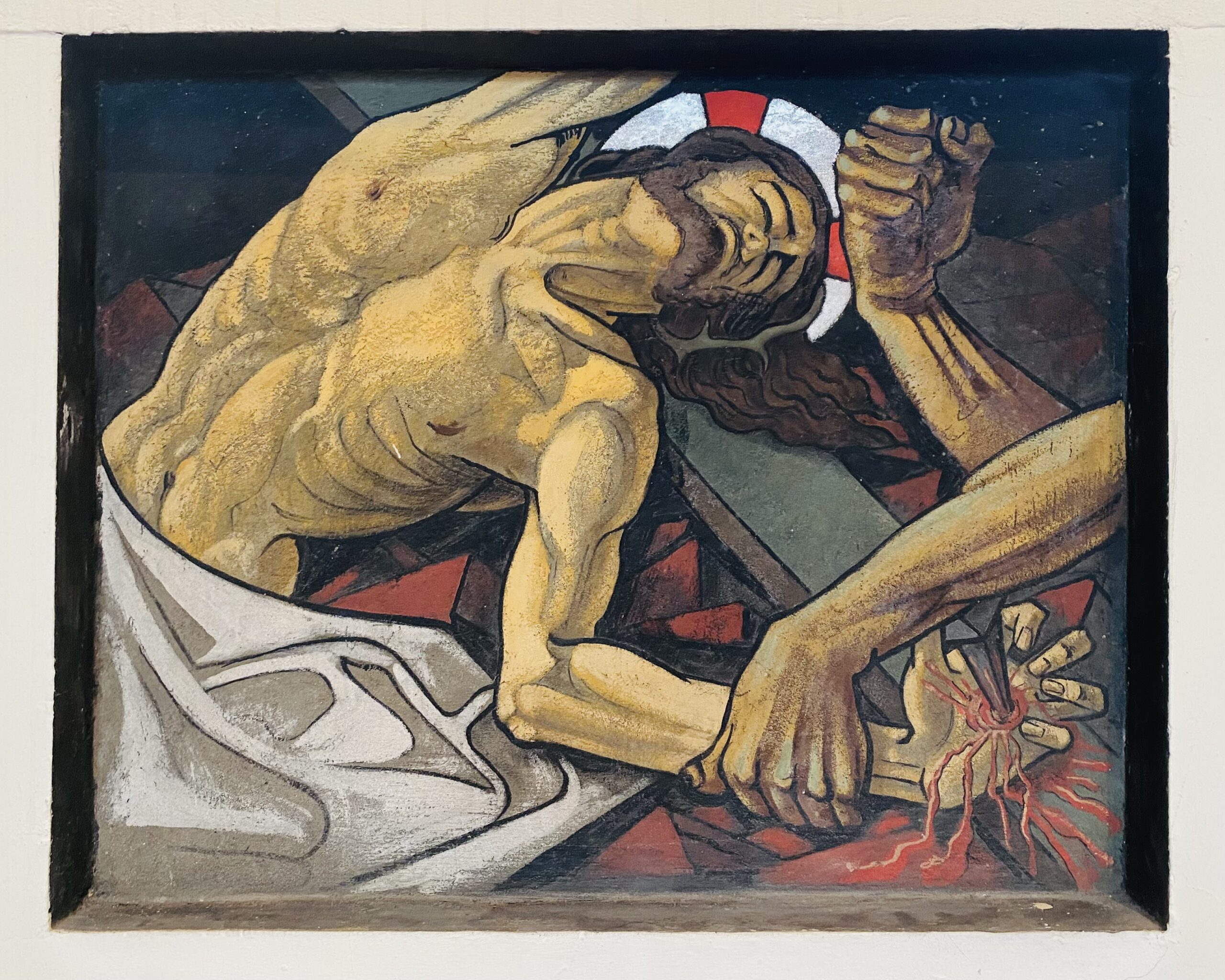

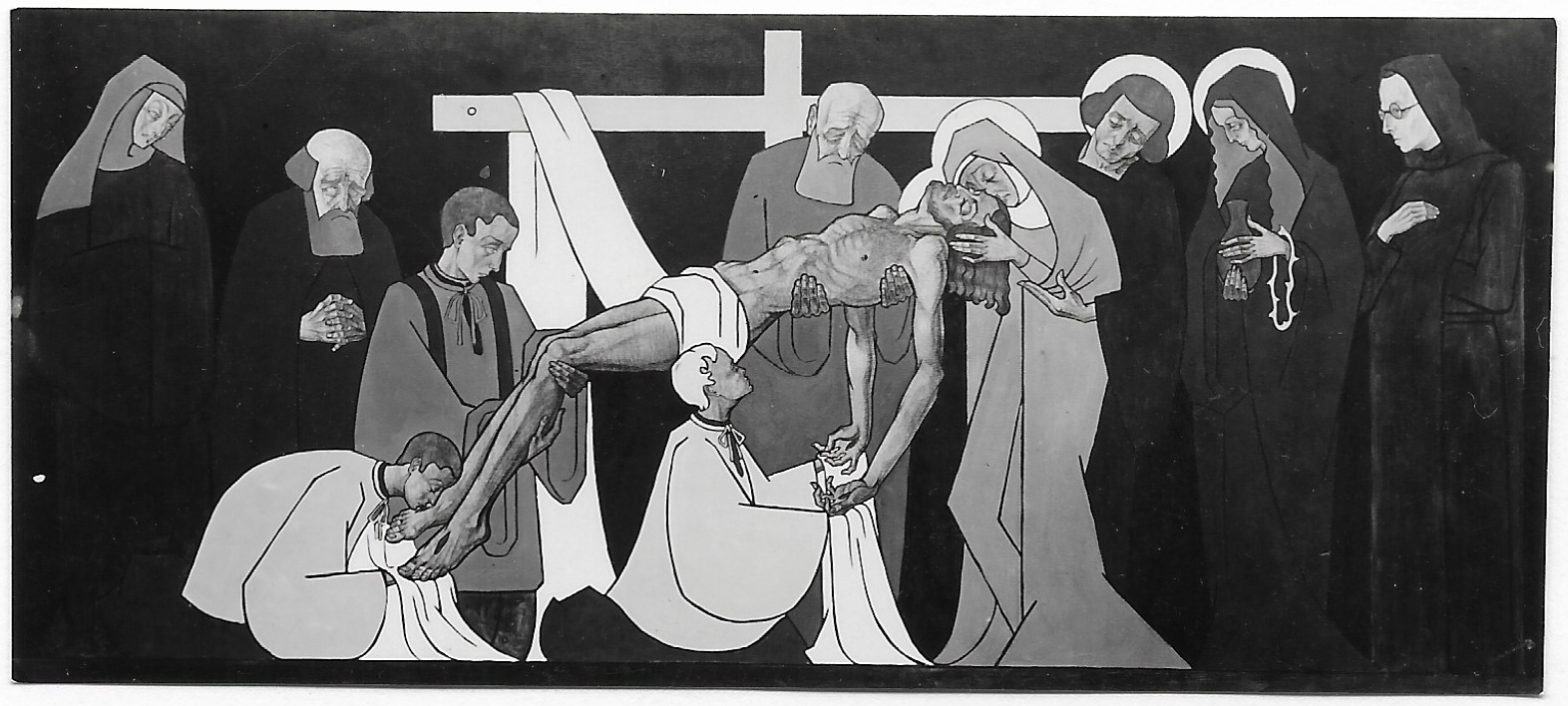

The zeal de Wit had for creating art to magnify the Lord was surpassed only by his concern to truly seek God (RB 58:7). The combined preference resulted in a cenobite living his most productive years as a gyroscopic sarabaite. His love for walls led him far beyond the cloister. “If I see a wall,” de Wit once told The San Francisco Examiner, “I jump upon it to paint it with frescoes. I often pray: ‘Please give me walls’” (26 March, 1941, 6). As usual, the desired reply from on high did not occur as often as the artist made the request. To guard against the acedia that often accompanies dry spells, de Wit would create smaller movable works. Even those would sometimes be of such large scale that it was a mere technicality not to designate them murals. A prime example is the expansive fifteen panel work, Quasi modo geniti infantes, created for Saint Ottilien Abbey, Emming, Germany in 1929. That sprawling depiction of the Eternal Spring will serve as the centerpiece for an exhibit of de Wit’s Bavarian years.

Scheduled to open 30 November 2025, Hidden with Christ in God: the Life and Art of Dom Gregory de Wit, will be the first retrospective of the artist in all of Europe. A similar exhibit was mounted in the United States by the Saint Tammany Art Association in Covington, Louisiana, 7 December 2019 — 25 January 2020. Curated by Jaclyn Warren, the exhibit was limited to works from the local area. Although a catalog was not published for the exhibit, it was mounted as a sort-of sequel to the first documentary on de Wit, Hand of the Master: The Art and Life of Dom Gregory de Wit (Stella Maris Films), created by David Warren in 2018.

With the logistics of gathering an international representation of works for a retrospective at Saint Ottilien beyond realistic expectations, it was decided by the curator, Fr. Cyrill Schäfer OSB, to limit the exhibit to works from the host monastery and the neighboring Saint Michael’s Archabbey, Metten. Both communities played key roles in the initiation of Dom Gregory into the world of Ecclesial art during the interbellum years of the 20th century. The exhibit will be composed only of works from that period. Fortunately, even that limitation provides ample material for an interesting collection.

While the retrospective of the German edition of the de Wit corpus is, like the Louisiana collection, limited to a specific time and region, a more comprehensive approach was desired by the curator. The catalog to be published for the exhibit by EOS Editions Sankt Ottilien will make available, for the first time, an extensive biography of the artist along with a borderless collection of art from across de Wit’s career. Although being authored by one person, it will be the culmination of work by a number of people over the course of many years. To help make the project as comprehensive as possible, it is hoped that others will join the number as virtual contributors through this crowdsource appeal for information.

As is true even when researching well known figures of history, surprising information is found among dusty forgotten files lost to even the most diligent of archivists. How much more is this true of those who may never be famous. Over the course of his 35-year interest in de Wit, the author of the forthcoming catalog, Edward Begnaud, along with the assistance of too many to be recounted here, has experienced the same. Since the embolisms of time affect the unknown even more than the known, the likelihood of lost physical fragments or forgotten bits of memories is far greater. The organizers of the upcoming de Wit exhibit, therefore, would like to make an appeal to the readers of NEXUS for information regarding the artist and his art. That there are works in private collections unknown to anyone other than the owner is highly plausible. Records of encounters with the perichoretic monk surely exist in monastic annals and family oral history. A sampling of some unresolved specific research points are included in the following list.

- It is thought that de Wit may have done work for Saint John the Baptist in Oostende and Saint Nickolas in Ypres, Belgium but no proof of either can be located.

- The artist mentions in his memoirs that he went to Tounai, Belgium for work but provides no specifics.

- It is known that de Wit spent some time at Maria Laach Abbey, Germany and at least a few days at the Abbey of Maredsous, Belgium. It is not known if he left any art at either monastery as he often did when visiting other places.

- In addition to the two mosaics designed by de Wit at Saint Laurence, Antwerp, there is a very traditional, albeit modern, icon of the patronal saint. Oral history of the parish attributes it to Dom Gregory. A signature is not included; nor is there any written documentation to substantiate the claim. Stylistically, there are indications of de Wit's hand. Documentation supporting de Wit's authorship would be valuable.

- There are very few known extant works from the years that de Wit spent as a hermit in Oberems, Switzerland from c. 1955 until his death in 1978. Any possible leads on work from those final years would be extremely valuable.

Any information leading to the resolution of these inquiries is greatly appreciated.

A research experience makes the organizers optimistic that crowdsourcing is a great aid to their work. After locating photographs of a heretofore unknown “Way of the Cross” created in 1931/32, Fr. Cyrill was able to establish that they were commissioned by Saint Joseph Church in Straubing, Germany. Unfortunately, there is no record of what happened to the set.

It is hoped that this appeal will add to the record of information about de Wit or perhaps the recovery of something lost. In the end, de Wit may still not attain the stature of famous but in the process, his good zeal will serve more generations who truly seek God.

Information may be emailed to: GregorydeWit.info@gmail.com.